The hidden life of Georgia: interview with Natela Grigalashvili

A conversation with the first female photoreporter of Georgia

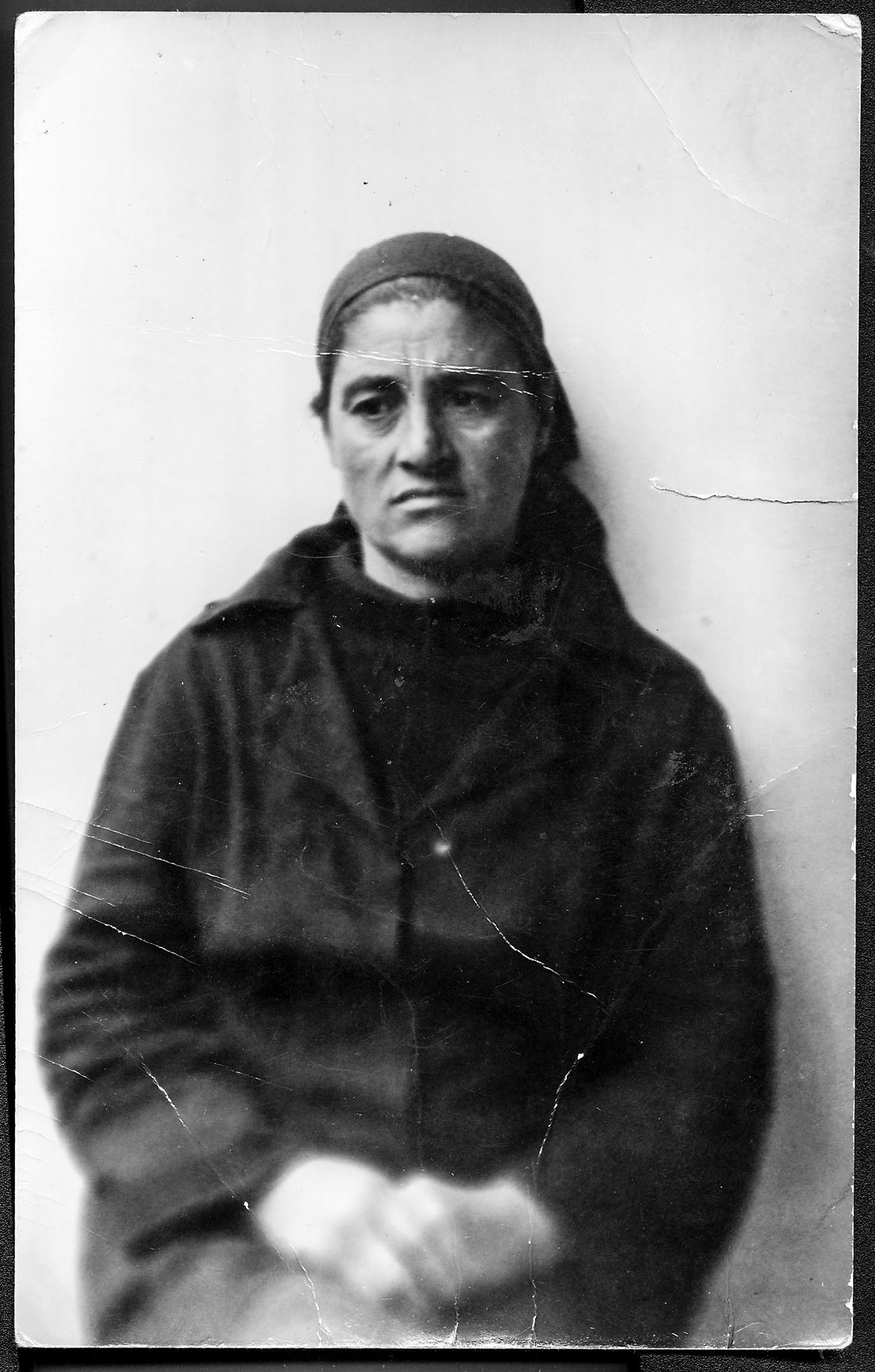

Just about two years ago I came across Natela Grigalashvili’s photos for the first time on the Instagram: I was immediately captured by the intimate portrait of a remote country, suspended in another time. Her shots are equally strong and delicate: they show the hidden life of the rural communities of Georgia, and the fatigue and daily routine of women in her country.

Natela was born in 1965 in Georgia. She lives in Tbilisi and she’s made a lot of photographic projects travelling all around the country: by doing so, she became the first female photojournalist in Georgia. We don’t speak the same language, and this interview has been translated several times through many emails. In the middle of a pandemic, the secret window opened by her photographs is like a breath of fresh air.

How did you start to photograph?

The reason why I started photography was cinema. I wanted to be a cinematographer. Growing up I loved movies. I remember old Soviet cinema magazines they had in our village library, I had some of them at home, too that I bought with my lunch money. I would read them over and over again. After finishing school I went to the capital, Tbilisi, to fulfill my dream. In order to become a cinematographer and pass the exams, I needed to learn photography.

I started going to the local portrait studio to learn about the technical aspects of photography. I was the only woman in a group of 24 people. At that time photography was not an appropriate profession for a woman, that’s why not many women were interested in it. Unfortunately, in the end, I could not study cinematography because it was too expensive and I ended up in a situation where I was completely alone and I had to support myself.

I stayed with photography but nowadays I’m happy it went like this. I love to communicate through my photos and I think I have more creative freedom than I would have had as a cinematographer.

The dream of cinema didn’t become true, but I do find your photos to be very “cinematic”: were you inspired by the work of some director or cinematographer when you first started your career? Did your inspirations change?

For a long time, even before I started photography, I was in love with Italian neorealism. I often watched movies of this genre on the TV. I think these movies had a big influence on me, especially at the beginning of my career as a photographer. I have to mention Georgian director Otar Ioseliani — I was in love with his movies, especially Once Upon a Time There was a Singing Blackbird.

I still love all of those movies that I loved when I was younger, but lately, I don’t have that much time to enjoy them. As time goes by of course the taste is changing, you find new inspirations and are fascinated by new stuff. Right now I like Abbas Kiarostami and I often watch his movies when I have time. I love his movie 24 Frames in particular.

Your photos are intimate, they achieve the “fly on the wall” style. How did you make your presence accepted in such a small reality, especially after leaving your village to study in Tbilisi?

Most of my projects are long term. I spend several years on each one of them. For me the most important part of working on the photo project is communication with people, then comes the photography. I love being around these people, spending time with them. Despite the fact that I’ve spent a big part of my life in the city I believe I’ve never lost a connection with my home village. I haven’t forgotten who I am and where I’m coming from. Maybe this is the reason why people who live in the rural areas accept me so easily: they don’t see me as a stranger, as someone who is different — and this is something they’ve told me many times.

One of the main themes in your work is the hidden life of small towns, remote villages, and disappearing communities in the mountains. There is always a feeling of nostalgia and also of being in front of a frozen, surreal world. Why did you decide to go back to your village, and what were your reasons not to leave?

As I’ve mentioned above, I left my home village and moved to the capital to continue studying when I was 16. Since then, I’ve been living in Tbilisi. It was an emotionally difficult process for me but I wanted to fulfill my dreams. When I came to Tbilisi I was completely alone, struggling to support myself. I grew up in a small house, at the end of the village, near the mountains and forest, in a calm environment and close to nature.

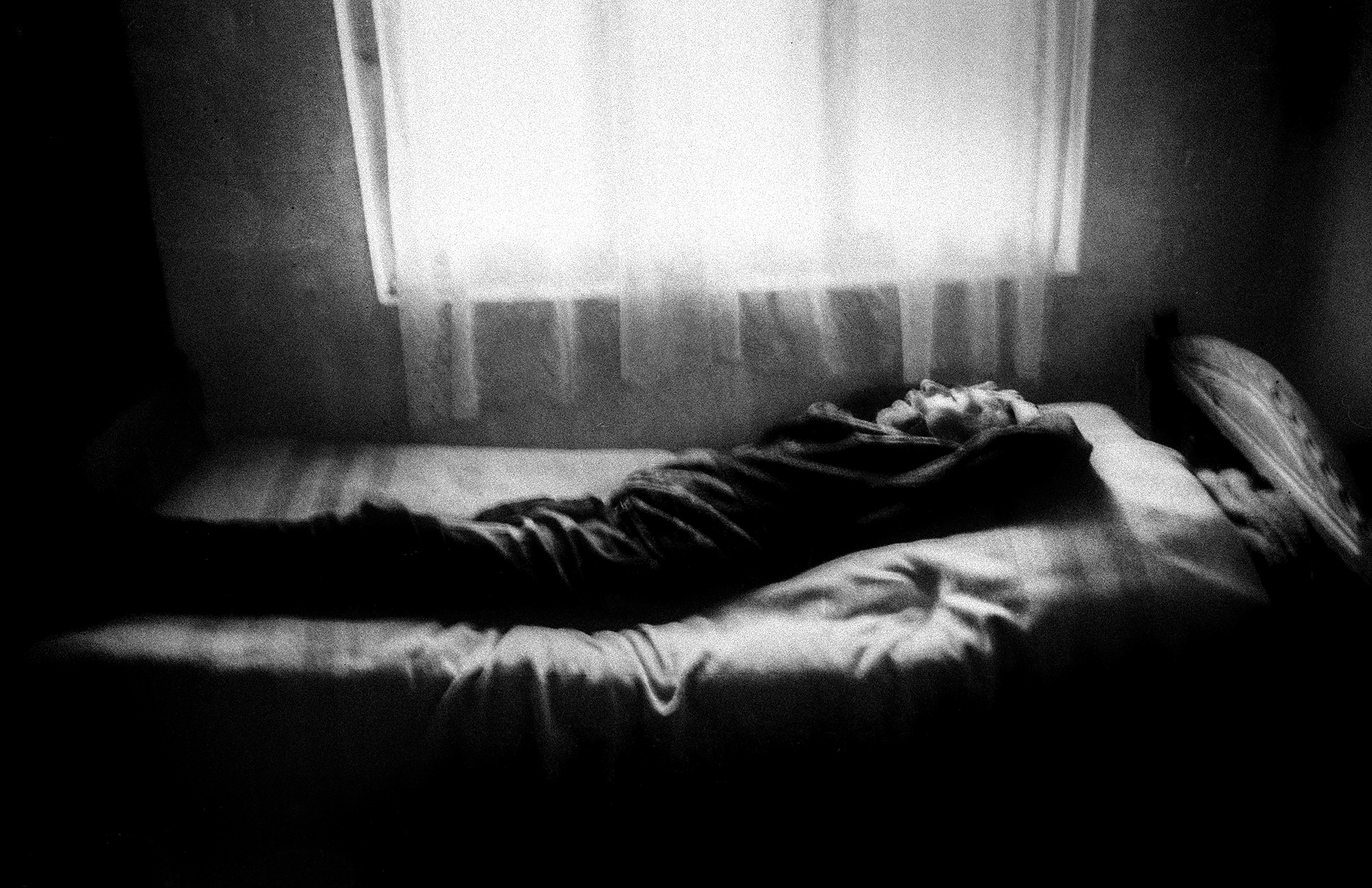

Suddenly I was in a big city, with huge block buildings and people, very different from those I grew up with. I felt really lonely and I started missing my home village and the people who lived there. I started going back to my village, Tagveti, every time I had a chance and started photographing everything there — places, people, etc. The reason why I was doing this was to have as many memories as possible when I would go back to Tbilisi. This is how my two long term projects — “Village of the Mice” and “The Book of my Mother”, were created. These two projects are from my home village that I’ve been photographing for more than 30 years.

For me, your style has its fundaments in reality, but most of the time it results to be dreamy. Do you prefer to shoot in analog or digital?

Nowadays I mostly use a digital camera, but for many years at the beginning of my career, I photographed analog black and white photos.

How does it feel to be the first female photojournalist in your country? What were the biggest obstacles you faced?

When I started photography it was not considered as a suitable profession for a female. That’s why my family was really unhappy when I started photographing. But as time went by they got used to it and were not protesting my decision. I can’t say that I had negativity from the strangers, they were just surprised, especially in the 80s and early 90s. When I went on the assignments for the newspaper articles my respondents often told me that they expected that the photographer would be an older man with a mustache and instead there was a young woman with a camera =)

You show a rural and poor reality, hard for its inhabitants. What is the political, social, and economic situation in your country?

I’m not an economist and I don’t know what the official numbers say, but based on my observation it’s getting more and more difficult to live in Georgia. Especially in the rural areas. That’s why there are so many people leaving villages and trying to move to the capital. The reasons are not only economical, but it’s also social. Basically, everything is concentrated in Tbilisi, while the regions are struggling and are not developing culturally, socially, and economically. Because of the unemployment and no chance of proper education youth are leaving the country to support their families from abroad.

What is the process behind a project? How do you find a fil rouge and choose to follow a specific subject?

I love to travel through the regions of Georgia. For several years, when I had just one day off from my everyday job I would just go to the bus station, read the location names on the buses, then choose one, would get on it, and go with it to the destination where it went. I tried choosing the places which would give me a chance to return the same day. I would talk to people who were traveling with me on the bus, ask details about their home villages, etc.

Georgian people are very kind and polite, and they always have so many interesting stories to tell about their villages. That’s how most of my project ideas are born. From talking to people who come from rural areas. If I got interested in a certain place or event then I would do additional research to gather as much information as possible. And then I start visiting the place, as often and as long as I could.

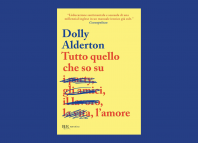

Can you tell us something about your project Book of My Mother? How did it start, and how did you deal with such a personal matter? How did you choose the right distance between you and your subject?

I started this project as soon as I started studying photography and got my first camera as a gift from my friend. We had a difficult relationship, my mother and me, and it got emotionally even worse when I left home. I constantly missed her and at the same time, I was feeling angry when I was in the city. Despite this, I tried to photograph her as much as I could when I was going back home. It took me years to realize that the bitterness that I had in my heart was not right. It helped me to overcome the past and that’s when the project Book of My Mother was created.

You often portray women’s daily life, capturing everyday rituals and small details. How it is to be a woman in Georgia? Do you have some kind of connection with other female photographers and artists within the country?

The Georgian art scene is not very big so most of the artists know each other. Of course, each life is different, but there are some basic details that I believe unite most of us, women in Georgia — artists or not we are still mothers, wives, etc. and quite often a big part of our lives goes to caring on children, doing home chores. It is an issue for a lot of women because this unpaid labor takes too much time and affects their personal development, career, and artistic work.

What are your future projects?

I currently plan to do several projects, one of them in Tbilisi. This is something new for me to because I’ve never done long term projects in the city. Let’s see how it goes.

{Here you can find the same interview in Italian}

Amazing artist, nice to find this background, good questions